Tokyo Underground

The Construction Series > Earthquake >Small > Ginza > Circular > Earth > Underground

If someone refers to the Captain

as “going underground,” the typical connotation

is that of the sleuth snooping through a seedy burg or random

less-than-reputable establishment. Certainly his exhaustive

survey last week of the Lip

and Hip “high quality touch club" in Kabukicho,

where shrewd negotiation cut the entrance fee by two-thirds,

would be a perfect example.

But

this week the

Captain is literally heading under Tokyo’s surface,

40 meters to be exact. Glance over his shoulder as he inspects

a massive Tokyo utility project that purports to be making

the city a safer and more enjoyable place.

But

this week the

Captain is literally heading under Tokyo’s surface,

40 meters to be exact. Glance over his shoulder as he inspects

a massive Tokyo utility project that purports to be making

the city a safer and more enjoyable place.

It is a typical central Tokyo

intersection. Office workers shuffle out of coffee shops;

cheap suit outlets troll for customers with fancy window

displays; taxis

and buses clog the roads from curb to median; and a construction

site - as all intersections in this modern metropolis seemingly

require - sits on one corner, white fencing surrounding the

property.

But this intersection in Toranomon is special

in a particular way: no column, scaffold, concrete mixer, or other

standard evidence of work ever shows itself from behind the

construction site's enclosure. The reason can be found below

- way below - ground level.

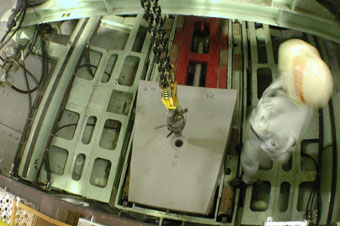

Stepping past the barrier and descending a

narrow spiral staircase to a temporary platform reveals Tokyo's

literal underworld. It is a stunning 20-meter diameter concrete

cylinder extending down for 40 meters. Light green hues reflecting

off the smooth concrete from mounted lights fill the scene

as workers move in and out of a temporary trailer and up and

down the single steel-cage elevator.

The

project, titled the Azabu-Hibiya Common Utility Duct

is a public works venture under the Ministry of

Land, Infrastructure and Transport that collects various utility lines into

a single trunk tunnel. Not only are Tokyo¹s endless streams of overhead wires slowly being reduced as a part of an effort to decrease earthquake susceptibility, the stunning scene makes for a unique tourist attraction.

A report provided by the Tokyo National Highway Office said that after the 7.3-Richter magnitude Kobe earthquake in 1995, which killed more than 6,000 people, similar ducts tended to move along with earth pressures and suffered little damage.

A report provided by the Tokyo National Highway Office said that after the 7.3-Richter magnitude Kobe earthquake in 1995, which killed more than 6,000 people, similar ducts tended to move along with earth pressures and suffered little damage.

The existence of a single underground "lifeline" during these times, the Ministry says, will increase the chances that vital services will continue to be supplied at the time of the disaster. By contrast the Kobe quake resulted in utility services going down. As well, emergency vehicles

being restricted access to troubled areas by downed and entangled

utility lines.

The Japanese Cabinet office's Central Disaster Management Council issued a report in December 2004 indicating that a major earthquake in Tokyo could result in 13,000 deaths and the destruction of 850,000 buildings.

A 2004 study by the Earthquake Research Committee indicated that there is a 70 percent chance that Tokyo will be hit by a major tremor within the next 30 years. The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 was the last large quake to strike Tokyo. About 140,000 people died amid falling buildings and subsequent fires.

Over 100 kilometers of roadway in Tokyo have been given similar treatment. Under Route 246, a completed duct that stretches from Aoyama to Akasaka has been in operation for 20 years. Plans are set for an additional 1,000 kilometers throughout the metropolis.

Public works projects are typically shrouded in secrecy. But this project is different.

Public works projects are typically shrouded in secrecy. But this project is different.

"A lot of Japanese citizens have this

idea that public works projects are not for the public,”

says Kiyotaka Yamana, who under the Tokyo Geo-Site Project promotional moniker arranges public tours and encourages

general awareness. “They (public works projects) are

notorious for having negative images attached to them. I am

trying to let the public know why they exist and what they

are being used for."

By

presenting these concrete works as fully open tourist attractions,

Yamana can show the public that taxpayer money is not literally being flushed down the drain.

During the two-hour tours, held a few times each year, visitors strap on

protective helmets and walk through a section of a completed

segment. The experience is similar to entering a science fiction

movie set; machines clank and hum as visitors proceed down

illuminated concrete arteries that appear to continue forever.

Colorful displays and placards along the path

tell the story of how the work has been performed. A handful

of the workers are on hand to answer questions.

Yamana

is always looking for “friendly” events to attract

visitors. Traditional Japanese theater performances have been

staged on a makeshift stage atop the bottom of the shaft.

As well, votive lights have been strewn along the tunnel floors

to create candlelit walks. Included among the visitors to

this subterranean world have been television crews and film-makers.

With the public associating public works with

past financial

busts like the Aqualine toll expressway - one of many

recent examples of bureaucrats citing inflated demand projections

to justify large project budgets - Yamana is trying to develop

a sense of openness to a practice that has typically been

very opaque.

With the public associating public works with

past financial

busts like the Aqualine toll expressway - one of many

recent examples of bureaucrats citing inflated demand projections

to justify large project budgets - Yamana is trying to develop

a sense of openness to a practice that has typically been

very opaque.

"Once people have a chance to visit, a

lot are amazed with what is inside, the size of the space,

the machines that are used, and the people who are doing the

work," Yamana explains.

Toranomon is the "launching shaft." The cylinder is a hub in which lateral utility tunnels emerge at its bottom in the directions of Azabu and Sakuradamon.

Theses tunnels are concrete-lined

by rings of reinforced concrete blocks, slightly curved to

fit into place around the walls. A large slurry tunneling machine,

with rows of teeth affixed to a rotating shield, bores its

way laterally through the generally sandy soil at a diameter that ranges from

five to seven meters.

The reinforced concrete blocks (about the size

of the tops of office desks) are pushed into place by jacks

attached to the back of the machine to form one ring of the

lining. Subsequent rings are added as the work, which follows

the centerline of the road above, continues laterally from

the hub. . Two hours is required to install a single ring.

A scaffold is then mounted slightly above the

bottom of the tunnels. In addition to providing a floor on

which workers can move, a center rail allows a train,

named “Pikachu,” to haul the blocks and various

bits of needed construction equipment as the work progresses

along the line.

The utility lines - such as gas, telephone, water, electric, and cable - are

designated by a specific color, are affixed along the walls.

As the name implies, the project extends from

the Tokyo districts of Azabu to Hibiya. Toranomon is roughly

in the center. Construction, which began in 1989, was recently

completed for the 2.8-kilometer segment between Azabu and

Toranonon. The additional 1.5 kilometers for the Hibiya segment

is expected to be completed by 2010. The project’s budget

is 42 billion yen, which corresponds to roughly 10 billion

yen per kilometer of road.

As the name implies, the project extends from

the Tokyo districts of Azabu to Hibiya. Toranomon is roughly

in the center. Construction, which began in 1989, was recently

completed for the 2.8-kilometer segment between Azabu and

Toranonon. The additional 1.5 kilometers for the Hibiya segment

is expected to be completed by 2010. The project’s budget

is 42 billion yen, which corresponds to roughly 10 billion

yen per kilometer of road.

The number of workers required is minimal. Only four are needed to operate the boring machine, while the site might include 25 in total at any given time.

Work was delayed at Hibiya for a short period in 2001 when a pile driven below the surface for the construction of a retaining wall discovered 240 stones from the Hibiya Gate of Edo Castle.

Digging

for the Hibiya segment started last year. The work has extended a little more than

800 meters, nearly reaching the moat of the Imperial Palace.

This distance contains a slightly uphill slope to a depth

30 meters below the surface. For

reference, the Yurakucho subway line crosses nearby at about

15 meters below the surface. In later stages, the work will

take a ninety-degree turn at the moat and continue another

580 meters to Hibiya.

Other benefits of the project include: the disappearance of

overhanging lines makes the metropolis more pleasing to the

eye; utility line longevity is increased by the lack of exposure

to natural elements; and the reduction in costly excavation

eases maintenance and increases pedestrian and vehicle flow.

"In central Tokyo, a lot of road construction

is taking place, causing traffic jams,” Yamana says.

“Here, a common utility tunnel is being placed under

major areas so that if one cable is cut off or some other

problem happens, a workman can go underneath and do the repair

work without having to dig a trench."

In

neighboring Saitama prefecture, Yamana likewise promotes the

Metropolitan Area Outer Discharge Channel under the

G-Cans Project title. This project, however, differs

slightly in scope from its Tokyo public works brother.

In

neighboring Saitama prefecture, Yamana likewise promotes the

Metropolitan Area Outer Discharge Channel under the

G-Cans Project title. This project, however, differs

slightly in scope from its Tokyo public works brother.

This 6.3-kilometer network is a series of inlets,

pumps, and massive underground concrete channels that funnels

rainfall runoff into the Edogawa River before it empties into

the Pacific Ocean.

For this project, Yamana has expectations that

reach beyond mere tours and theater shows; he wants to show

the world the appeal of Japan’s concrete

spectacle.

Spectacular pictures of large support columns and

meandering channels contained on the G-Cans Project

Web site have caught the attention of Life magazine and ABC

News (Australia). Yamana hopes Hollywood comes calling next.

"My dream,” he says, “is for

the next 'Die Hard' movie to have Bruce Willis

jogging through one of the concrete channels.”

Sweet concrete dreams…

Note: All photos taken during a tour of

"The Azabu-Hibiya Common Utility Duct."

The Construction Series > Earthquake >Small > Ginza > Circular > Earth > Underground