Unwinding the Mystery of the Gyroball (Part I)

The Gyroball > Part I > Part II > Part III > Part IV

A corked bat? A little pine tar on his palm? The Captain tried every trick to get an edge in his playing days.

This week he is coming out of retirement to learn how to properly toss a "gyroball." Folks, given that every media organization covering this story has completely botched it, let's say this together: s-c-o-o-p.

This week he is coming out of retirement to learn how to properly toss a "gyroball." Folks, given that every media organization covering this story has completely botched it, let's say this together: s-c-o-o-p.

Daisuke Matsuzaka is 26 and sports a crown of spiky hair. He stands at 182 centimeters, weighs 85 kilograms, and throws a gyroball.

He throws a what?

Based largely on Matsuzaka's dominant performances in the World Baseball Classic and the 2.13 ERA and 200 strikeouts he posted with the Seibu Lions last season, last month the Boston Red Sox submitted a bid for the whopping sum of 6 billion yen just for the privilege of negotiating a contract with him.

To his Japanese fans, the right-hander is known simply as "Daisuke." When he pitches, his follow-through often ends with a high kick of his right leg. His fastball checks in at a lofty 150 kilometers per hour. Knees buckle at the sight of his curve. His change-up makes hitters look foolish. And his gyroball...

"It is a pitch with a gyro spin," explains Dr. Ryutaro Himeno, the director of the Advanced Center for Computing and Communication at the science and technology research institution Riken in Saitama Prefecture.

Himeno, in a brown blazer and ruffled hair, says that the pitch is delivered such that its release from the fingers sends it toward home in a tight spiral, much like a fired bullet. He uses the "football pass" analogy to explain the proper means for unleashing a gyroball.

In the late '90s, Himeno started simulating how a gyroball moves on a computer. In 2001, he co-authored the book Makyu no Shotai (The Truth about the Supernatural Pitch) with baseball instructor Kazushi Tezuka.

"Tezuka is the 'Godfather' of the gyroball," Himeno says of his associate, who operates sports clinics in Tokyo and Osaka. "I just proved that the pitch exists."

"Tezuka is the 'Godfather' of the gyroball," Himeno says of his associate, who operates sports clinics in Tokyo and Osaka. "I just proved that the pitch exists."

Matsuzaka, however, complicates things by being secretive in public about whether the pitch is really part of his arsenal, saying that he maybe experiments with it on occasion or that he doesn't throw it at all.

His coyness has spawned rumors and guesses on the traits of the pitch.

American newspapers, whose stories typically compare the pitch's elusiveness to that of a ghost or the Loch Ness Monster, have approximated the degree of the pitch's break, graphically showing it making a sweeping turn as it crosses the plate - a movement so large that it exceeds even that of a curveball. Others have suggested that it slices back in the opposite direction.

Is this beast for real?

Conversations with the pitch's pioneers, two very different people working in two very different worlds, make reaching some kind of concurrence on the gyroball's characteristics and Matsuzaka's connection about as easy as trying to hit a Matsuzaka pitch - any one of them.

In Himeno's office, the professor has a plastic bottle that has had both of its ends trimmed. With red tape lining its edges, the former vessel is now a gyroball training tool in the shape of a cylinder.

In Himeno's office, the professor has a plastic bottle that has had both of its ends trimmed. With red tape lining its edges, the former vessel is now a gyroball training tool in the shape of a cylinder.

"When throwing a fastball," Himeno says, rolling a baseball off the tips of the fingers on his right hand, "the palm will face the direction of the pitch upon release. But for the gyroball, the release will cause the palm to face the pitcher's body, his fingers slightly curling."

After explaining that a proper gyro grip is the same as that of a standard fastball, Himeno, takes the bottle up into his hand as if he were to throw a pass. He follows through, rolling the tube to the tips of his fingers and bringing his hand down in front of himself almost like a karate chop.

The cutting motion that sends the ball spinning toward the plate is so pronounced that the hurler's thumb, Himeno says, will often wind up pointing to the ground after the follow through, not too dissimilar from the gesture that supposedly spelled the end for some gladiators. (Slow-motion videos of Matsuzaka's form are often scoured in Internet chat rooms for that thumb point, which ostensibly will indicate the equivalent of an Abominable Snowman sighting.)

"Unlike most other pitches," Himeno says, "the wrist is not snapped when it is delivered."

From hand to home, two forces work against the ball: a drag force (caused by friction) retards the velocity and gravity brings it back to earth.

From hand to home, two forces work against the ball: a drag force (caused by friction) retards the velocity and gravity brings it back to earth.

A pitch changes its direction because of its rotation. The curve, for example, is delivered with topspin, which for a right-handed pitcher pushes the ball down and to the left. Likewise, the backspin on a fastball gives it a slight push upward to fight gravity (though not enough to cause it to actually rise).

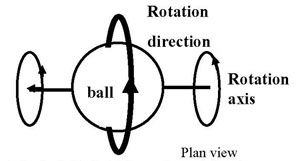

Himeno says that for a properly thrown gyroball the direction of the ball's rotation will be exactly perpendicular to the direction of travel.

Since these two velocity vectors do not intersect, which is not the case for a curveball or fastball, there will be no additional push influencing the ball in any direction.

Mother Nature then says that upon its release the gyroball will be slowed by friction and felled by gravity only. There will be no curving, cutting, slicing, or dicing. Just drag and drop.

The Gyroball > Part I > Part II > Part III > Part IV