Daido Moriyama: Shinjuku Drifter

The Sleuth Series > Detective Bar > Daido Moriyama > Alberto Fujimori

Though behind a typewriter is where

the Captain has made his name in the field of journalism,

he isn’t too shabby with the shutter button. His personal

hostess “upskirt”

photo album is a testimony to that.

Daido

Moriyama is another matter; he is a respected professional

photographer. Join the Captain this week as he speaks with

Moriyama about shooting the darker side of Tokyo’s Shinjuku

Ward.

Daido

Moriyama is another matter; he is a respected professional

photographer. Join the Captain this week as he speaks with

Moriyama about shooting the darker side of Tokyo’s Shinjuku

Ward.

A silver ashtray sits next to his

pack of Ark

Royal Sweets on the coffee shop table.

Photographer Daido

Moriyama retrieves one of the thin brown cigars and grabs

his lighter. After he takes a few puffs, the air in front

of his well-worn face is soon filled with gray smoke.

He then pulls his trusty point-and-shoot Ricoh

GR1s from his back pocket. The ease of his motion and its

heavily nicked body implies that his camera

is always at the ready.

Moriyama is in his element. The coffee shop

is in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Ward, the place where he has

made his name as a photographer.

“I am very interested in its stripped-down

form,” he explains. “Shinjuku gives a very mixed

feeling with all its various kinds of people. It is very realistic

and intriguing.”

The images he captures often show everyday

people and everyday things in a manner not to be found in

the average Tokyo tourist guidebook. Whether by using blur

or cropping, Moriyama’s bleak and lonely black-and-white

pictures have garnered him the reputation as one of Japan’s

great modern photographers.

Moriyama’s most recent exhibition “Moriyama-Shinjuku-Araki”

at the Tokyo Opera City Gallery was a joint show with fellow

photographer Nobuyoshi Araki. Featuring many shots taken during

a walk through Tokyo's Shinjuku Ward during an August day,

the shoot was a chance for the pair to recreate a prior trip

to Okinawa.

“We

liked the time we spent together in Okinawa,” Moriyama

says. “So we decided to do it again in Shinjuku. We

just hung around taking photos.”

“We

liked the time we spent together in Okinawa,” Moriyama

says. “So we decided to do it again in Shinjuku. We

just hung around taking photos.”

Tokyo is a city of contradictions in motion,

and no place typifies that more than Shinjuku. The Tokyo Metropolitan

Government building sits opposite the entertainment district

Kabukicho - notorious for its prevalent gangster

activity, brothels, and strip clubs. In between is Shinjuku

Station, the city’s busiest train hub.

Unlike Araki, who generally uses color photography

to target women in various settings, Moriyama’s focus

is capturing Shinjuku’s blend of old, new, and unpredictable

in monochrome.

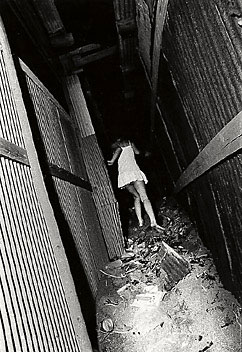

The people of Moriyama’s work are often

faceless, covered in shadow or obscured by blur. It is not

unusual for a backside - a couple descending stairs, for example

- to be the image's main element.

His lens, often slanted at random angles, doesn’t

shy away from typically unappealing bits of the urban cityscape.

Building exteriors - of which maintenance is rarely a priority

in Tokyo - are shot in all their drabness. Webs of utility

lines and mesh fencing are often in view. A storm drain

grating can be the focus of a shot.

Moriyama sees Shinjuku as a place on the edge.

Ikebukuro to the north and Shibuya

to the south lack realism, he says. It is Shinjuku’s

"depth" that he finds appealing. “When I walk

through Shinjuku taking photos," Moriyama explains, "I have a feeling of excitement and fear.”

One of his favorite haunts is Golden Gai, a

throwback to how Tokyo looked decades ago. Wedged between

Kabukicho and Tokyo’s largest gay area, Golden Gai is

a block of bars (some offering less than five seats) within

decrepit wooden structures packed so close that a single stray

match might one day send the entire complex up in smoke. “It

is one of the places that gives that realistic look,”

he says.

Many

of Moriyama’s images imply action of some kind has happened

or is about to happen - even if that is truly not the case.

The feeling is that of drifting in and out of a scene: a hostess

draws a cigarette from her pack as two of her colleagues watch

for customers near their club's brightly lit entryway; a woman

moving through a crowded street scene casts a glance over

her right shoulder, the upper half of her bare backside showing

a few tattoos with the rest obscured by shadow.

Many

of Moriyama’s images imply action of some kind has happened

or is about to happen - even if that is truly not the case.

The feeling is that of drifting in and out of a scene: a hostess

draws a cigarette from her pack as two of her colleagues watch

for customers near their club's brightly lit entryway; a woman

moving through a crowded street scene casts a glance over

her right shoulder, the upper half of her bare backside showing

a few tattoos with the rest obscured by shadow.

“I have to be aggressive to take photos

in Shinjuku,” says Moriyama, who might shoot 20 rolls

of 36-exposure film on an average day. “In Shinjuku,

you take photos quickly. Judging the quality of a particular

shot doesn't come first sometimes.”

Such an approach has gotten him into trouble.

During the shooting for his book Shinjuku three years

ago, Moriyama found himself explaining his actions to police

officers on more than one occasion. But that’s Shinjuku,

he says.

Born in Osaka, the 67-year-old Moriyama was

influenced at an early age by the work of American photographer

William Klein.

“I realized that pictures have the power

to move people,” he says. “I never thought that

pictures could be so cool.”

Klein’s influential work, as typified

in his 1956 book New York, is known for its blurry images

and the variety of angles and perspective used.

“He takes pictures straight toward people,

very naturally,” Moriyama says of his protégé.

“William's pictures are not intentionally blurry. He

shoots the photo and then enlarges it as he develops the film.

That is why it becomes blurry.”

As

most photographers know, the cropping of a raw image is a

key to a successful photo. Moriyama is no different. As an

example, he points at a slightly tilted photo in the Moriyama-Shinjuku-Araki

exhibition book of the bottom half of a pair of female legs

walking away from the camera. Moriyama explains that by just

showing the area between her black skirt and high heels the

image is more effective in that it forces the viewer to use

his imagination.

As

most photographers know, the cropping of a raw image is a

key to a successful photo. Moriyama is no different. As an

example, he points at a slightly tilted photo in the Moriyama-Shinjuku-Araki

exhibition book of the bottom half of a pair of female legs

walking away from the camera. Moriyama explains that by just

showing the area between her black skirt and high heels the

image is more effective in that it forces the viewer to use

his imagination.

In spite of Moriyama having produced dozens

of photo books during his four-decade career, he is often

associated with one picture in particular - that of a dog.

Titled “Stray Dog,” the mysterious half-tone street

shot shows a large black canine, piercing eyes and dropped

lower jaw, seemingly readying itself to defend its turf.

“I was staying in a Tohoku in a hotel,”

he remembers of the day over 30 years ago. “In the morning,

as soon as I walked out of the hotel, I saw a dog, and I took

the picture. I never thought that it would be famous.”

This photo is from a period when grainy, or

“rough,” images were his focus. Moriyama admits

that greater detail and less roughness can be found in his

snapshots of recent years. A close-up shot of a store's headless

mannequin in a skirt, shell necklace, and feathery fur jacket,

for example, is clear and crisp.

Occasional

overseas exhibitions of Moriyama’s work have resulted

a moderate international presence. Six years ago the San Francisco

Museum of Modern Art toured almost 200 photos, including “Stray

Dog,” through the U.S. and Europe.

Occasional

overseas exhibitions of Moriyama’s work have resulted

a moderate international presence. Six years ago the San Francisco

Museum of Modern Art toured almost 200 photos, including “Stray

Dog,” through the U.S. and Europe.

Moriyama acknowledges that perhaps his photos

of Japan are not what the typical outsider expects, but any

previous perceptions a viewer might have are out of his hands.

“I don't think that I am taking photos

that are not representative of Japan,” he says. “I

want to express the realness of Japan. I want to show what

is really going on.”

In the coming months, he plans on having an

exhibition in Tokyo of photos he shot in Buenos Aires. Inertia

will be in control thereafter.

“My work is endless,” he says.

“As long as the world exists, I want to take snapshots.”

The ashtray is now filled with butts, ashes

sprinkled about. Moriyama’s shoulders are slumped as

he sits in the chair. His straight dark hair, parted down

the middle, hangs over his eyes. He is one of his own photographs

just waiting to be snapped.

Note: Tomo Nakano and Yukiko Kuwamura contributed

to this report from the Tokyo Bureau. Photos 2-4 courtesy

of Daido

Moriyama.

The Sleuth Series > Detective Bar > Daido Moriyama > Alberto Fujimori