NHK's Revenue Getting Slammed

Back in the early '80s, the Captain pioneered the world's first door-to-door Betamax repair service. Market forces eventually caused him to re-evaluate that venture and focus on being a newsman. Billions of readers are glad he did.

This week he is profiling another door-to-door system facing similar challenges: broadcaster NHK's fee collection system.

This week he is profiling another door-to-door system facing similar challenges: broadcaster NHK's fee collection system.

Wham! The sound of slamming doors is becoming increasingly common across Japan.

Nihon Hoso Kyokai (NHK), Japan's only non-commercial public radio and television broadcasting network, has recently been forced to re-evaluate its policies after a series of scandals have caused large numbers of viewers to boycott paying the subscription fee collected door-to-door.

"NHK is moving on to implement new radical reform measures to enhance moral behavior and strengthen compliance among our employees," explains Masaya Shimokawa, deputy director of the programming department . "In order to impress viewers that NHK has changed, we need to communicate that programming has also changed."

Through internal and programming changes, NHK hopes to re-establish its reputation as Japan's most trusted broadcaster and convince its viewers to once again resume dutifully paying the fee, the basis of a unique revenue system that contrasts with its advertising-based broadcasting brethren.

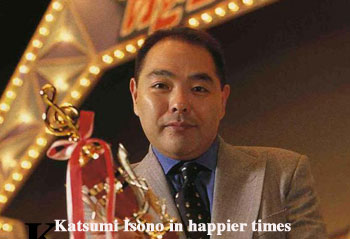

Trouble started last year for NHK with the arrest of Katsumi Isono, a program director accused of embezzling funds earmarked for production costs. The case grew to include other instances of misappropriation by other staff and was compounded by a story in the Asahi newspaper in January that reported that political pressure caused NHK to edit a controversial piece on war crimes of the Imperial Army around the time of World War II. NHK officials have staunchly denied making any such edits.

By the end of September, nearly 1.3 million subscribers had refused to pay the monthly fee, which is either 13 or 21 dollars (depending on the subscriber package), as a protest. Consequently, NHK president Genichi Hashimoto says that revenue from viewership charges for the six months through September will be around 23.7 billion yen ($213 million) short of the company's projection. Further, NHK expects revenue losses of up to $450 million for the fiscal year ending next March.

To atone for the admitted embezzlement scandal, NHK has reduced retirement bonuses for eight board members who resigned in April. Additionally, former NHK president, Katsuji Ebisawa, who ultimately resigned in January, and two other executives have had their retirement money suspended.

NHK plans on offering a new program in October that will help viewers understand NHK's role with its first female vice president, Taeko Nagai, answering viewers' questions. As well, programming changes that will attempt to further meet the expectations of the public will be discussed next spring.

NHK plans on offering a new program in October that will help viewers understand NHK's role with its first female vice president, Taeko Nagai, answering viewers' questions. As well, programming changes that will attempt to further meet the expectations of the public will be discussed next spring.

This crisis, however, will not disrupt NHK's services to the public.

Takashi Suzuki, director of the financial department, says, "We will steadily implement the goals and objectives outlined in the 2005 business plan."

These goals include round-the-clock delivery of news, weather, sports and education programming and the launch of a digital terrestrial broadcasting service.

Similar to broadcasters in the US, NHK's competitors are privately owned and supported by advertising. Each company is associated with a national newspaper to allow for the sharing of news resources. But with its far-reaching news outlets and large revenue - nearly fifty percent greater than its nearest rival Fuji Television Network, Inc. - NHK is Japan's broadcasting Godzilla.

After transmitting its first radio signal in 1925, NHK was incorporated in 1950 as Nihon Hoso Kyokai (NHK) under Japan's Broadcast Law. Today it includes five television and three radio channels in Japan.

Like the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the fee is collected from people in possession of a television in lieu of advertising.

The fee goes back to before World War II when the purchase of receiving equipment required a government license. This was eliminated with NHK's establishment and the fee system's implementation.

Refusal to make fee payments, for which there is no penalty, has precedent. In addition to the over one million people who decline primarily due to economic hardship, disruption in NHK's signal from airplanes or trains has been occasionally cited as reason for not paying.

Critics point to NHK's reform measures as simply papering over the cracks in the organization, and maintaining that a lack of confidence in NHK remains.

Kenichi Asano, professor of Journalism and Mass Communications at Doshisha University, sees NHK's problems as being in the untouchable image it has attained within Japan's media and the deficiency in accountability within NHK's current leadership.

"Unlike the BBC, it has not been acceptable for anyone in the media to criticize NHK," he says. "An ombudsman or third-party system should be implemented to regain the public's trust."

But even if NHK regains all of that trust, it may not recover all of its lost revenue.

Yoshifusa Momose, associate director of NHK's audience services department, explains that while outrage fueled the initial boycott, there is now a growing feeling that there's no obligation to pay the fee.

"Many subscribers," Momose says, "are taking a wait-and-see attitude toward how NHK will change."

Note: A similar version of this article ran in Variety on October 10th as a part of a package commemorating NHK's 80th anniversary.