Independence Comes to East Timor

For most Americans the Fourth of July is an opportunity to give thanks to the men and women responsible for the freedoms they have enjoyed over the past two centuries. To signify this they will engage in any of a number of typically American activities, perhaps a parade, a fireworks show, or even a backyard barbecue. It's a personal choice; in essence, a freedom in itself.

The Captain is no different. Acknowledging independence for him typically centers around the combination of a dozen strings of firecrackers, his collection of plastic model airplanes, and a bottle of malt whiskey. In preparation for the big day, he takes his favorite slacks - stitched in a US flag pattern - to the cleaners during the last weekend of June. A true patriot, he is.

The Captain is no different. Acknowledging independence for him typically centers around the combination of a dozen strings of firecrackers, his collection of plastic model airplanes, and a bottle of malt whiskey. In preparation for the big day, he takes his favorite slacks - stitched in a US flag pattern - to the cleaners during the last weekend of June. A true patriot, he is.

This week the Captain ventures to East Timor, a place where independence is but two months old. There, through the lives of street vendors in the capital of Dili, he finds a nation and its people slowly adjusting to their newfound freedom from Indonesian occupation.

The Telstra pre-paid phone cards are fanned out in the salesman's right hand in a set of six. Any and all foreigners exiting the nearby ANZ bank ATM machine are his target. To each one he waves the cards and utters a small attention grabber: "Sir!" He does this all day. It's his job.

"I can get 20 cents a card as profit for each of the $25 cards I sell," says the 25-year old salesman, sitting in a blue plastic chair at the bank's entrance and smoking a cigarette. "Looking for another job now is worthless. There is nothing else."

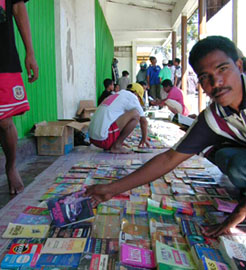

He has been at this work for 2 years. Similar tales of futility can be told by any of the hundreds of vendors that crowd the edges of the dusty streets of East Timor's capital city of Dili. Their merchandise might vary - local vegetables, fresh fish, magazines, baseball caps, bootlegged CDs, imported cigarettes, or beer, but their story is always the same: We may have independence, but we don't have money or a reasonable way to make a living.

In an early morning ceremony on May 20th, East Timor became the world's 192nd independent nation. President-elect - and former freedom fighter - Xanana Gusmao afterwards swore in a 24-member cabinet and Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri. It was this half-island nation's new beginning after over 25 years of brutal occupation under Indonesia.

This is the culmination of a process that began with a UN-organized vote for independence in August 1999. Since then East Timor has been under the control of the United Nations. The UN's report card for their work in looks good thus far: there is peace; thousands of displaced refugees are slowly returning to their homes; a transitional government is in place; and, vital infrastructure is slowly being constructed after it was destroyed by the vacating Indonesian militias.

This is the culmination of a process that began with a UN-organized vote for independence in August 1999. Since then East Timor has been under the control of the United Nations. The UN's report card for their work in looks good thus far: there is peace; thousands of displaced refugees are slowly returning to their homes; a transitional government is in place; and, vital infrastructure is slowly being constructed after it was destroyed by the vacating Indonesian militias.

But when the independence celebrations stop and the UN packs its bags for home, East Timor will not be left as a fully self-sufficient nation from the start. It will take time before the people can stand on their own without the doting hand of international assistance. The reasons are simple.

For one, they are poor, probably the poorest in all of Asia. Recent unemployment estimates reveal that nearly 3 out of every 4 people in search of work can't find a job. For another, it will be quite a few years before the nation can develop the means to exist economically without the assistance of foreign aid, presumably at least until it can exploit its natural resources of oil and natural gas. Add to this the conflicting views held by Gusmao and Alkatiri on the direction that the East Timor government should take from the opening and a cloudy beginning for this nation looms.

In the meantime, there is street vending.

The vendors are men and women, boys and girls. The simplest sales tools are the weaved mat and a smile. The best location is a sidewalk heavily trafficked by foreigners; they are likely workers for non-governmental organizations, one of the embassies, or private companies involved in reconstructing East Timor, in other words, people with cash.

In between the ANZ bank and one of Dili's larger intersections, a book salesman spreads his large selection of Indonesian Microsoft software training manuals, English dictionaries, guitar playing manuals, and steamy pulp fiction cover-styled novels in rows onto a green and brown mat at the entrance to store selling jewelry. Next to him is a large, round man with his Indonesian newspapers and magazines arranged for readers to pause for a quick check of the headlines or a longer squat on their haunches for a read of the latest news. Further on, a woman and her young daughter arrange lemons in pyramids.

For others, like the aforementioned phone card salesman, mobility is the best means. Durte uses a green pushcart to peddle his bottled water, beer, and cigarettes. On an average day Durte will ring up sales totallying $10. A pack of Marlboros from his cart goes for one dollar. "In the last few months, there has been nothing [for me]," laments the 35-year old, slumped over his cart and peering from beneath his visor.

For others, like the aforementioned phone card salesman, mobility is the best means. Durte uses a green pushcart to peddle his bottled water, beer, and cigarettes. On an average day Durte will ring up sales totallying $10. A pack of Marlboros from his cart goes for one dollar. "In the last few months, there has been nothing [for me]," laments the 35-year old, slumped over his cart and peering from beneath his visor.

This section of the street is near one the busiest intersections in Dili. During business hours, the area is continually teaming with honking taxis, slowly roaming the streets looking for fares, and people jutting in and out of the many stores while picking up supplies.

"I really need the training to develop

skills so I can have a shop of my own," Durte adds and

then pauses to turn toward the entrance of the JAPE Department

Store that his cart is sitting in front of. The store is owned

by an East Timorese man and sells everything from housewares

to bicycles. "This [vending cart] is only a small business,"

he sighs.

Still, even for some of the owners of many of these brick and mortar businesses, times are tough. "We opened 6 months ago," says the owner of a bakery just down the street from JAPE. "Business has been very slow."

But the big supply stores, restaurants, and markets along this road, and all throughout Dili, are what the street vendors see as their dream, their future. The majority are owned by East Timorese, but usually by East Timorese that have acquired management skills and business knowledge after spending time overseas.

Of course, most East Timorese live off the land or the sea - even Gusmao himself often speaks of his dream of becoming a pumpkin farmer - and coffee is one of the nation's few exports. But, it will be education and basic business knowledge that will be the key to developing East Timor and realizing the dreams of these vendors.

To the East Timorese, successfully getting out from under the Indonesian occupation was the first step. The memories of the more than 200,000 people killed by the fighting and disease that followed Indonesia's invasion of 1975 have not faded. Now they want to learn all that they can before the international community sets them free into the wild.

To the East Timorese, successfully getting out from under the Indonesian occupation was the first step. The memories of the more than 200,000 people killed by the fighting and disease that followed Indonesia's invasion of 1975 have not faded. Now they want to learn all that they can before the international community sets them free into the wild.

After the UN arrived in East Timor, a small employment base was established with the opening of restaurants, shops, and hotels, catering to the needs of the aid workers. The demand now for such things slowly disappears with each UN flight that departs from Dili's airport.

To this point, in a sense then, East Timor has been babied, or coddled. Now it is the people's turn. It is up to them and their government to make a prosperous future for East Timor.

"I want my experiences with the UN to be good," says Joseph, a 24-year old interpreter. "I want to increase my qualifications. It will be important for the beginning of our country. I want to learn how to do this and how to do that. As we are now, we are down."