A Casino Grows in Tokyo

On a typical weekday night, the streets on the west side of Tokyo's Shimbashi Station are alive with activity. Jewelry salesmen hocking necklaces and bracelets compete for sidewalk space with lottery ticket sales booths. Taxis line up for fares. Salarymen slowly filter into the hostess and snack clubs off the main streets.

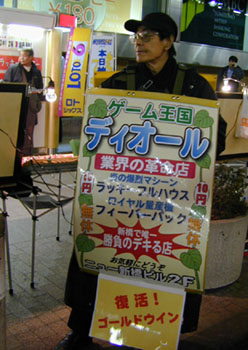

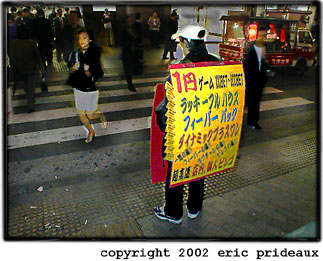

Mixed in are middle-aged men wearing advertising sandwich boards. They slowly pace the streets and sidewalks. The boards are decorated with playing cards or roulette wheels. Each board is for a different establishment. The boards promise gambling action for as little as ¥10. Small maps give directions to the location of each "game kingdom," or casino.

Mixed in are middle-aged men wearing advertising sandwich boards. They slowly pace the streets and sidewalks. The boards are decorated with playing cards or roulette wheels. Each board is for a different establishment. The boards promise gambling action for as little as ¥10. Small maps give directions to the location of each "game kingdom," or casino.

Today, legal gambling in Japan is limited to horse, motorboat, bicycle, and motorbike racing. A number of other activities, such as the lottery, pachinko, and mahjong, are classified as "amusements" and are legal. Casinos though are illegal in Japan.

How then is this activity possible? Reikichi Sumiya, a yakuza expert and journalist, explains of their existence, "Wherever there's gambling in Japan, there's the yakuza."

But unlike days gone by, the yakuza's involvement in gambling is not the big story. Rather, it is that the whole industry is suffering. The situation is so severe that it is even hitting the gangsters themselves. Sumiya relates, "Before the yakuza boss drove a BMW. Today he drives a domestic."

On a national level, nearly half of all racing operators lost money in fiscal 2000. Declining interest and a staggering economy are to blame. This is a serious situation because municipal governments have traditionally relied on profits from these operations as part of their budgets. To fix these shortfalls, legalized casinos are being proposed in Japan. But the ones now operating illegally are pretty interesting in their own right.

Generally, the yakuza operate the casinos and they are all illegal. Indeed, the yakuza and gambling in Japan have become synonymous over the years. Even the name "yakuza," which dates back to the eighteenth century, has its origins in gambling. It comes from a hand in a card game played with hanafuda (flower cards). One losing combination in the game is the card numbers 8, 9, 3, or in Japanese: ya, ku, sa.

The casinos are loosely based on the same exchange-of-goods-for-money principal as pachinko parlors. Casino chips used in the gambling action are exchanged for cash at a shop nearby. But that is where the similarities end.

The casinos are usually found in the same sorts of buildings that accommodate hostess clubs and massage parlors. Each casino is about as big as a bar or restaurant. Doormen regulate customers by sticking to a strict "members only" policy that usually prohibits foreigners.

The casinos are usually found in the same sorts of buildings that accommodate hostess clubs and massage parlors. Each casino is about as big as a bar or restaurant. Doormen regulate customers by sticking to a strict "members only" policy that usually prohibits foreigners.

One frequenter of the Shimbashi casinos, Hideki Yamamoto (not his real name) says of the casino business in general, "The police will go out and bust a different place once a week. So each casino probably will have to close down after one or two years. Then they will find a new location."

Because they are frequented by businessmen, Tokyo's Shibuya, Shinjuku, Ikebukuro, and Roppongi areas have the highest concentration of casinos. Yamamoto says that the police have gotten more strict in these popular areas recently. Therefore, some casino operations have moved to Shimbashi where the police are not as prepared to deal with them.

To prevent from being on the receiving end of an unfriendly visit from the police, the yakuza use a communication system run through a network of scouts. Young apprentice yakuza with mobile phones watch the moves of the officers at Atago Police Station - the station responsible for Shimbashi. Yamamoto says, "If the owner of the casino is given information that the police are on the move, then the casino might close for a while."

As a result, Shimbashi's streets may one month be filled with sandwich boards promoting blackjack, baccarat, and roulette at such establishments as Millennium, Gold Coast, and Paradise. However, the next month the action might just be limited to Dior.

Most casinos are losing money. Since the average casino patron succumbs to the odds, he winds up piling up huge debts. A lot of times he accepts loans to keep playing. But because of the tough economic times (and the fact that he continues to lose) he is unable to repay the loans. Add to this the threat of being closed down by the police and a grim situation develops. Sumiya sums up the business by saying, "The risk is big."

Most casinos are losing money. Since the average casino patron succumbs to the odds, he winds up piling up huge debts. A lot of times he accepts loans to keep playing. But because of the tough economic times (and the fact that he continues to lose) he is unable to repay the loans. Add to this the threat of being closed down by the police and a grim situation develops. Sumiya sums up the business by saying, "The risk is big."

Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara has made the most noise on the legalized casino front by announcing his intentions of constructing one or more casinos in hotels on Tokyo's waterfront in Odaiba. Governors from Osaka, Hiroshima, and Miyazaki are also in favor of considering casinos for their jurisdictions.

The hope is that a series of trendy, fashionable, and exciting Las Vegas style casinos marketed to young people would spur fresh interest in gambling and replenish government coffers.

A preliminary estimate from the Japan Casino Academy has indicated that between ¥50 billion and ¥120 billion in tax revenue would be generated per year if six public casinos were to open in Odaiba.

But will it happen? Ishihara would first have to overturn Japan's law prohibiting gambling. Some seem confident that his popularity and political clout will be enough to get the measure approved in Tokyo. This will get the ball rolling and many other parts of Japan will then have casinos as well.

Of the possibility, Sumiya warns ominously, "In the Edo Period, a lot of people lost their homes and sold their daughters into prostitution because of gambling losses. That's why it was banned in the first place."

Note: Eric Prideaux, Mark Sinclair, and Edward Gelband contributed to this report.