Japan Loves Cambodia

At Kobe, a Japanese teppanyaki restaurant in Phnom Penh, diners watch as their Cambodian chef cuts, chops, and grills prawns, beef, and squid. With the price of the meal per person being equal to a month's wage of the average Cambodian worker, the clientele is mostly foreign businessmen. They sip beer and sake as the grill sizzles and the chef skillfully works his knives. Kobe is one of about a half dozen Japanese restaurants in Phnom Penh. Just up the street and through the whirl of motorbikes, smoke, dust, and street vendors, a CD shop sells bootlegged copies of Japanese pop sensation Hikaru Utada's latest album. Not far away the Bayon Market offers a selection of Japanese groceries.

Taken individually, the meaning of these events is practically nothing. Japanese restaurants, food, and culture are everywhere in the world, even the third world. But in looking at them together and given that Cambodia has been the location of wars and conflicts over most of the past 30 years, they are symptoms of how Japan is influencing this Southeast Asian nation today.

Taken individually, the meaning of these events is practically nothing. Japanese restaurants, food, and culture are everywhere in the world, even the third world. But in looking at them together and given that Cambodia has been the location of wars and conflicts over most of the past 30 years, they are symptoms of how Japan is influencing this Southeast Asian nation today.

In Japan, it is difficult to open a newspaper these days and not see an article about private or government aid work being done in Cambodia by Japan. To mention only a few; Sophia University's ongoing restoration of Angkor Wat in Siem Reap, the recent completion of a $56 million bridge across the Mekong River in Kampong Cham, the ongoing expansion of Phnom Penh's water treatment facilities, the school construction work being done by many NGOs, the landmine removal projects, and the monetary contributions for the demobilization of Cambodia's military.

Complementing this work is the frequent coverage being given by Japanese television on topics ranging from Angkor Wat to the widespread poverty and prostitution plaguing Cambodia. For now, Cambodia is a hot topic in Japan, and there are a lot of people from Japan working to ensure that this interest will continue.

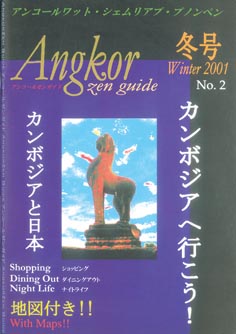

"We want everyone to love Cambodia," says Emi Uchizumi, editor of the Japanese language guide AngkorZen. The quarterly Cambodia-based publication includes restaurant reviews, interviews, and feature articles. It has a slick and colorful layout and prints 10,000 copies per issue. Its first issue was printed in April of last year.

"We want everyone to love Cambodia," says Emi Uchizumi, editor of the Japanese language guide AngkorZen. The quarterly Cambodia-based publication includes restaurant reviews, interviews, and feature articles. It has a slick and colorful layout and prints 10,000 copies per issue. Its first issue was printed in April of last year.

The magazine is dedicated to tourists and business people visiting Cambodia. Until recently, getting people to visit Cambodia was not an easy thing to do. Minister of Tourism, Veng Sereyvuth, knows this very well. In an interview with the Japan Times during a visit to Japan last year, he said that tourism is crucial to developing Cambodia's economy but that many tourists are hesitant to visit the country. The problem lies in its recent past.

Most of the last three decades have been filled with nothing but war and violence. Included in this has been the civil war between 1970 and 1975, the brutal reign under the Khmer Rouge that followed over the next four years, the civil war to expunge Vietnamese troops between 1979 and 1989, and current Prime Minister Hun Sen's overthrowing of Prince Ranariddh's government in 1997.

Sereyvuth has been trying to change this violent image by marketing Cambodia's cultural assets and emphasizing Cambodia's current relative safety. And until terror dropped down on the United States last year, he was doing quite well. In recent years, tourist arrivals are up between 20 and 30 percent. Japanese tourists are within the top five in terms of number of visits.

Uchizumi emphasizes though that Japanese people have been in Cambodia for many years. "But it has been thirty years of pent up demand waiting to get to the temples of Angkor Wat," she says of the recent interest. "Many of the places you see on TV were no-go areas even in the '90s. This is what happens when a closed-up country opens up to visitors, like Cuba and Vietnam in the '90s."

The greatest example of the attention Cambodia is receiving is the existence of "Tomb Raider," the Hollywood blockbuster from 2001 that featured Angela Jolie running, swinging, and jumping her way through the ruins of Angkor Wat.

"Check Vanity Fair or other magazines," Uchizumi adds. "Cambodia is it, for now. It's hip and has street-cred. People think they are so cool to walk around New York City or Tokyo with a landmine or Heart of Darkness t-shirt."

"Check Vanity Fair or other magazines," Uchizumi adds. "Cambodia is it, for now. It's hip and has street-cred. People think they are so cool to walk around New York City or Tokyo with a landmine or Heart of Darkness t-shirt."

The recent rise in tourists and the list of ongoing aid projects, however shouldn't insinuate that Cambodia is all of a sudden an absolute panacea for sightseeing and a paradise for foreign investors. Government corruption runs rampant. Landmines, though mostly removed from tourist areas, still exist (government estimates put the figure at around 4 million). It is not uncommon for political candidates to be murdered before elections. Also, the shooting of firearms by Khmers for recreation is considered part of the culture.

Still, Uchizumi maintains, "Readers are so surprised that Cambodia is such a normal country with ordinary things like fashion designers, artists, tennis courts, golf, and mad dirt bikers. We are trying to get the message out the message to the entire world that Cambodia has everything."

And thanks to the work of one man from Japan, remote Cambodian villages now have the Internet as well.

"We want to develop computer training. To show that the digital divide - the gap - can be narrowed. To prove that the Internet can be anywhere. That is the key to developing," Tokyo-based Bernie Krisher says of his project that brought the Internet to the northern village of Rovieng. The village of subsistence farmers may not have electricity, telephone lines, running water, or high skills in the Internet's main language of English, but they do now have the opportunity to communicate with the rest of the world.

Of all the work foreign work being done in Cambodia, none impresses more than the philanthropic work of Krisher and his nonprofit groups American Assistance for Cambodia and Japan Relief for Cambodia. A former Tokyo bureau chief for Newsweek and creator of the pioneering Japanese tabloid Focus, the articulate and composed Krisher has been dubbed "a one-man United Nations." His work has been featured in such publications as AsiaWeek and the New York Times.

In his village Internet project, called "Village Leap," Apple donates a computer and solar panels, costing $1,700, provide 6 hours a day of computer use. A satellite dish donated by Shin Satellite of Thailand then connects the system to the Internet. Though getting approval from government authorities for satellite communication outside of Cambodia was at first a struggle, the project has been fully endorsed by Prime Minister Hun Sen. In a letter of thanks to Krisher he referred to it as "contributing to broadening the knowledge of our next generation of leaders." But the benefits of the project don't stop with just Internet access.

In his village Internet project, called "Village Leap," Apple donates a computer and solar panels, costing $1,700, provide 6 hours a day of computer use. A satellite dish donated by Shin Satellite of Thailand then connects the system to the Internet. Though getting approval from government authorities for satellite communication outside of Cambodia was at first a struggle, the project has been fully endorsed by Prime Minister Hun Sen. In a letter of thanks to Krisher he referred to it as "contributing to broadening the knowledge of our next generation of leaders." But the benefits of the project don't stop with just Internet access.

Once a month, a nurse and a Massachusetts Institute of Technology media lab volunteer from Phnom Penh's Sihanouk Hospital Center of Hope spends 2 days in Rovieng. With the satellite connection joining them with Harvard Medical School, health care consultations are given to villagers. This is invaluable aid that the people in the village would not otherwise receive.

The hospital itself is another Krisher project. The two-story structure with outpatient center and 40 beds is probably Cambodia's finest. The organization Hope Worldwide runs the facility and funds half of its budget of over $100,000 a month. A private Japanese donor gives the remaining half.

A sustainable budget is a consideration of his Internet project as well. In order for it to be a feasible and worthwhile pilot program, it is going to have to have a source of income. That is where silk comes in.

During the 1970s, Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge regime destroyed, amongst other things, the tradition of silk weaving. Today, students weave silk scarves and sell them as e-commerce through their web page. The sales of scarves go to a pig farm and the sales of the pigs will eventually support the system. He hopes the scarf sales will one day generate $2,000 a month in revenue.

Much of the aid work in Cambodia from Japan, or any other outside nation, is through government channels. But Krisher doesn't prefer that method. "I make all the decisions," he says. "I like to do things with private donors."

After retiring from journalism (a career that first brought him to Cambodia), Krisher decided it was time he gave something back. But make no mistake that this 70-year old is merely a Santa Claus in spectacles and suspenders. He is about teaching and not making people dependent. "On my first trips to Cambodia," he remembers of his first relief efforts in the early 1990s following the Paris Peace Accord, "I brought food, medicine, and money. We started handing out money. They were at the bare subsistence level. But they became dependent [on the money]."

After retiring from journalism (a career that first brought him to Cambodia), Krisher decided it was time he gave something back. But make no mistake that this 70-year old is merely a Santa Claus in spectacles and suspenders. He is about teaching and not making people dependent. "On my first trips to Cambodia," he remembers of his first relief efforts in the early 1990s following the Paris Peace Accord, "I brought food, medicine, and money. We started handing out money. They were at the bare subsistence level. But they became dependent [on the money]."

After establishing the English language Cambodia Daily newspaper seven years ago, whose mission is "to establish a strong foundation for a free press and train journalists," he began securing operating funds for the Future Light Orphanage just outside Phnom Penh. Krisher says of the 285 children at the orphanage, "In Cambodia the word 'orphan' can have a number a meanings; a child whose parents could not raise kids, a child of parents too poor to take care of their kids, children of depressed women, children whose mother had been raped, children without fathers."

Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times approached Krisher a few years ago, indicating that he wanted to write a story about malaria in Asia. Krisher suggested Cambodia. Kristof's lead for the story described the death of a young child in a Cambodian village. Readers sent in money and it became the genesis for Krisher's ongoing mosquito net program. "So when I get a certain amount of donations. I order the nets for $5 a piece from the World Health Organization. One net is for a family of three. So I say, 'Save 3 lives for $5.'"

His "Put a Roof over Their Heads" program constructs schools for $24,000 in remote villages. Donors fund half the project and through a World Bank matching program in the field of rural development the remaining funds are obtained. Thus far funds have been secured for over 200 schools and half those have already been built. The donors have come from the United States, Singapore, Britain, and Japan. Japan's Nippon Foundation put up matching funds for 100 schools alone.

"The best people were killed by Pol Pot; all the lawyers, teachers, doctors, and professors," he says of Cambodia's recent past. "The people running the country today survived because they were not the best. These people are mediocre. They don't run their jobs, agencies or ministries well. They are corrupt. I see no hope that these people can be reformed or changed."

"The best people were killed by Pol Pot; all the lawyers, teachers, doctors, and professors," he says of Cambodia's recent past. "The people running the country today survived because they were not the best. These people are mediocre. They don't run their jobs, agencies or ministries well. They are corrupt. I see no hope that these people can be reformed or changed."

At present, the majority of Cambodians live in poverty as laborers, farmers, fishermen, soldiers, nurses, teachers, or housewives. But Krisher believes that his programs have the potential to provide for a better life in Cambodia.

"These are pilot projects to prove that you can do this, not only in Cambodia, but anywhere in the world," Krisher says of the motivations for his work. "My investment is in the future and the children."

Note: Bernie Krisher may be reached at bernie@media.mit.edu. Angkor Zen may be contacted at angkorzen@yahoo.com. The Cambodia Daily is available for free at Cafe de Pres in Hiroo, Tokyo.