Donning the Robe

After a hard day of chasing deadlines,

the Captain’s concept of “spiritual healing”

typically means ensuring that the cap on his bottle of Southern

Comfort is nice and tight before placing it back in the cabinet.

But

this week he’s entering a temple to chat about spirits

of a completely different kind with a Buddhist priest. The

incense is already burning, why don’t you step on inside?

But

this week he’s entering a temple to chat about spirits

of a completely different kind with a Buddhist priest. The

incense is already burning, why don’t you step on inside?

As incense emanates from a

few ceramic pots, Buddhist priest Gakushin Tsujimoto settles

back on the tatami mat of Renkeiji, the temple over which

he presides.

The temple is built into the residence he shares

with his wife, son and daughter. It is a modest home tucked

within a residential neighborhood above Yokohama

Bay. Nearby is the cemetery that Tsujimoto uses to provide

any of his deceased followers a proper Buddhist sendoff to

the afterlife.

With a buzz haircut, the stereotypical standard

in his line of work, and a gold sash over his gray robe, he

points at a series of posters hanging on the back wall above

a stack of purple pillows. There are a half-dozen in total,

each with black Chinese characters running down along the

white pages. One reads: “To change a person's mind you

have to take action.”

The always-smiling 62-year-old explains: "These

have been made so people can get hints inside my theories."

They work as sort of an icebreaker, an introduction

to Tsujimoto’s feelings and way of thinking. This is

necessary in his occupation; after all, many of his daily

duties deal with some rather intangible ideas.

"It is always hard to get people to understand

what I am trying to say,” he says. “I try to let

people understand happiness but they cannot understand easily.

Mentally and spiritually, I have to take care of people who

need help or guidance."

In summary, the 350 families under Tsujimoto’s

watch are expecting him to provide a balm for the soul. It

has been this way for priests in Japan for hundreds of years.

But

recent times have seen an added wrinkle in the average priest’s

robe. Accusations that the priesthood is increasingly becoming

a shroud for a lucrative business are common. For Tsujimoto,

he is old school; his priority rests with the well being of

his followers.

But

recent times have seen an added wrinkle in the average priest’s

robe. Accusations that the priesthood is increasingly becoming

a shroud for a lucrative business are common. For Tsujimoto,

he is old school; his priority rests with the well being of

his followers.

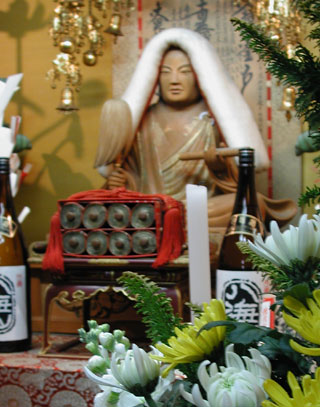

His daily routine always begins with a bang

- or more accurately, with the striking of a small cylindrical

gong - to signify the start of a prayer session. The gong

sits next to a large kneeling pillow slightly offset from

a butsudan, or small Buddhist memorial. A statue of

Nichiren, a 13th century priest who taught that all people

- regardless of race - could attain enlightenment, is perched

at the top of the tiered wooden structure. Sake

bottles, flowers, scrolls, and various other decorative

pieces occupy the lower shelves.

Once the prayer session of bowing, hand gestures,

and uttering of appropriate phrases is complete, Tsujimoto

then begins tending to his flock. He either receives them

at the temple or heads off to their residences.

Tsujimoto wants to get inside the minds of

his followers and help them with any troubling issues. Common

concerns are relationships, finance, and work.

Oftentimes his most difficult task is getting

them to turn off any preconceptions they may have of him and

simply listen to what he has to say. “New followers

can be rude; they think they are superior," he explains.

"So communication can be difficult. But after they start

to understand basic concepts on what it means to live, what

religion is, they start to learn how to listen to my thinking.

In the beginning is the hardest part."

The periods of ohigan, which literally

means "other shore" but implies transcendence to

enlightenment, in March and September and obon - the

time in July and August when the spirits of ancestors are

said to drift back to this world - are some of his busiest

times. During these periods, family members pay their respects

to their ancestors' graves, offering flowers or incense. "I

pray for the person's spirit in order to heal the spirit,"

Tsujimoto says of his role.

Perhaps Tsujimoto's biggest task is the administration

of funerals, which tend to be controversial undertakings in

Japan due to their extraordinary cost.

When

all is said and done a typical Japanese funeral goes for a

lofty 3 million yen - roughly four times that of the United

States. The industry is worth 1.5 trillion yen annually.

When

all is said and done a typical Japanese funeral goes for a

lofty 3 million yen - roughly four times that of the United

States. The industry is worth 1.5 trillion yen annually.

The point of contention is that the emphasis

has turned to money. The business is so competitive that the

practice of florists, funeral companies, and priests providing

kickbacks to hospital staff for information on fresh corpses.

"Regrettably I have to admit the business

aspect is more important for funerals and religious occasions,"

says Tsujimoto, who presides over around 20 funerals a year.

"In Japan, funeral companies take the lead and not the

priest so in this regard it is difficult to insist that religion

should come first. It is a sad thing for me."

The funeral is a three-step process for the

priest. On the first night of the deceased's passing, Tsujimoto

will find himself praying next to the person's sleeping pillow.

In days past the next day would entail a prayer session that

would run "all through the night" but recent times

have seen that prayer period revised down to one or two hours.

The last step is the cremation.

"After the burning of the body, the bones

are picked up (by members of the family)," says Tsujimoto

of the remains that will eventually find their way to the

family's cemetery plot. "Then I pray again. That is the

last prayer."

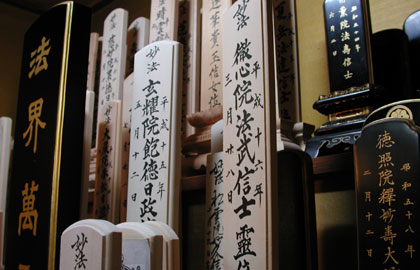

The element that likely raises the greatest

ire during the procedure is the preparation of kaimyo, a black

rectangular plaque with six to twelve characters. The characters

make up the person's posthumous Buddhist name.

Before the Edo Period (1603-1867), kaimyo was

reserved for priests when they were ordained. Since then they

are used to represent the achievements laymen after death.

The formula is simple: the higher the number of characters,

the greater the prestige...and the greater the charge. A recent

survey by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government found the average

kaimyo fee to be 400,000 yen.

Public

outrage over such exorbitant fees four years ago caused the

Japan Buddhist Federation to issue the following statement:

"Kaimyo is not a commodity to be traded for money. Any

money or gift you give to your priest or temple is strictly

a donation you offer voluntarily."

Public

outrage over such exorbitant fees four years ago caused the

Japan Buddhist Federation to issue the following statement:

"Kaimyo is not a commodity to be traded for money. Any

money or gift you give to your priest or temple is strictly

a donation you offer voluntarily."

But the reality is usually quite different.

Relatives of a deceased person with the task of paying for

kaimyo usually experience something akin to looking over items

on a restaurant

menu, with each character having a price attached to it.

Tsujimoto, who guesses that his typical kaimyo charge is about

300,000 yen, is adamant that he chooses the characters and

merit is the determining factor.

"I receive an amount that the family can

afford," he says. "I do not give a specific price.

The main point is that the money is a donation. It is given

to express appreciation; it is a cleansing gesture, a symbol

of my work but also an appreciation for the dead person."

Renkeiji began from scratch four decades ago.

The area was not heavily developed but a few residents wanted

to establish a new temple. This was soon after Tsujimoto,

who entered the priesthood because he was not physically intimidating

as a child and just wanted a healthy life, had completed his

priest schooling.

"I

was in a normal family, not a religious family," he remembers.

"In Buddhist schools, there are two types of people:

Those whose family is connected to a temple already and those

who are not."

"I

was in a normal family, not a religious family," he remembers.

"In Buddhist schools, there are two types of people:

Those whose family is connected to a temple already and those

who are not."

Today, things are still rather humble. The

temple, which from the outside could be easily mistaken for

a regular residence were it not for the small sign near the

entrance, relies on donations from the followers for survival.

Though Tsujimoto has managed to boost the number

of followers at his temple steadily over the years, he is

worried about the state of Buddhism in Japan as a whole. Modern

society might be leaving it behind.

“People's sense of values have changed,"

he says. "People are putting less emphasis on Buddhism.

Instead of religion, concrete matters are more important.

Something you can see has become more important than something

that is invisible.”

Tsujimoto thinks that individualism imported

from the West following World

War II has had an impact.

“Many people are moving from the suburbs

to the big cities," he says. "By moving to the city

they are losing their connection to their family, and the

family size gets smaller.”

Though by far the majority of priests inherit

their temple from their family, it is not uncommon to hear

of downsized office workers donning robes in recent years.

Tsujimoto says that such a transition is difficult given the

lack of experience the new priests possess.

As for the future of Renkeiji, Tsujimoto expects

his son to eventually take over his role. “But I am

not certain what he will do," Tsujimotos says. "He

has his own thinking."

Note: Kazuko Maruyama and Kaoru Shimizu contributed

to this report from the Yokohama Bureau.